marți, 23 decembrie 2008

Festivalul Uniunii Teatrelor Europene la final

Festivalul UTE, organizat de Teatrul Bulandra a ajuns la final.Am reusit sa vad un numar de 12 spectacole, cele mai reusite fiind, in ordinea vizionarii : " Unchiul Vania" de A.P.Cehov, productie a Teatrului Maghiar din Cluj, regia Andrei Serban, "Lear" de W.Shakespeare, Teatrul Bulandra, regia Andrei Serban, "Trilogia vilegiaturii"de Carlo Goldoni, Piccolo Teatro, Milano, "Minciuna", un spectacol de Pippo Delbono ( Fondazione del Teatro Stabile di Torino si Teatro di Roma), "Viata si destin" dupa Vassili Grossman, regia Lev Dodin, Maly Teatr, Sankt Petersburg, "Richard III "de W.Shakespeare, regia Tompa Gabor, Teatrul Maghiar din Cluj, "Ancheta" de Peter Weiss, regia Gigi Dall'Aglio, Teatro Due din Parma. La capitolul dezamagiri : European House- "Prologul lui Hamlet fara cuvinte", regia Alex Rigola, "Antigona"de Sofocle, regia Anna Badora, Schauspielhaus, Graz, "Amedeu sau Scapi de el cu greu" de Eugen Ionescu, studio 24-Roger Planchon.

vineri, 7 noiembrie 2008

Piccolo Teatro di Milano si teatrul de arta

6 noiembrie, Festivalul UTE, Bucuresti

Piccolo Teatro di Milano si Teatri Uniti au prezentat in cadrul Festivalului UTE "Trilogia vilegiaturii" de Goldoni.O dovada ca teatrul de arta facut de profesionisti adevarati nu a murit.Fara artificii regizorale, fara video proiectii si nuduri, fara inovatie de dragul inovatiei.Doar actori - si ce actori! - in slujba textului condusi de un regizor- actor si el in aceasta productie.Piccolo Teatro a reusit pentru o seara sa ne reaminteasca ca in anul 2008 se mai poate face teatru de arta.Arta pentru toti, asa cum a visat Strehler!

sâmbătă, 1 noiembrie 2008

"Unchiul Vania" pur si simplu minunat!

31 octombrie, Teatrul Odeon, Bucuresti.Teatrul Maghiar din Cluj a prezentat in cadrul Festivalului UTE, "Unchiul Vania".Cuvintele sunt prea sarace pentru a caracteriza acest spectacol.Pur si simplu minunat!Acest spectacol merita sa faca inconjurul lumii.Intreaga distributie merita un premiu de excelenta.Multumesc, domnule Andrei Serban pentru inca un moment splendid de teatru!

joi, 11 septembrie 2008

"Unchiul Vania" in turneu la Budapesta si Bucuresti

vineri, 5 septembrie 2008

marți, 2 septembrie 2008

Turandot, Royal Opera, Covent Garden, regia Andrei Serban

Andrei Serban's production of Puccini's Turandot is one of the jewels of the Royal Opera's repertoire.Twenty-two years after it was first given at the Los Angeles Olympics, it remains a grand spectacle and a great show, with Sally Jacobs's opulent designs and F. Mitchell Dana's atmospheric lighting.And in its most ambitious outreach project to date, the Royal Opera broadcast the performance on big screens in the open air around the country, including Lake Windermere for the first time, to an estimated audience of 25,000 people.

Before the show, the Royal Opera's Assistant Chorus Master Stephen Westrop led the audience in the Covent Garden Piazza in singing Nessun dorma, with help from three tenors from the Royal Opera Chorus, Elliot Goldie, Luke Price and Andrew H. Sinclair, to which the audience seemed to respond with enthusiasm.

For all its popularity, Turandot is in many ways a strange creation on Puccini's part. At times it feels more like a pageant than a conventional opera, but rather than try to obscure this aspect, Serban's production revels in it. The enormous red ribbons at the beginning, the grand, multi-tiered main set that houses the macabre chorus, and the dramatic masks: all these still look as vibrant as ever, suggesting that we'll be seeing another 22 years of the production. The direction is unfussy, perhaps occasionally lacking emphasis for the main characters, but there are nice touches, such as wheeling the dead body of Liù across the stage after the union of Turandot and Calaf at the end.It's a shocking moment that switches the closing emphasis onto the slave girl, who has died for her love for Calaf - and as it happens, Liù had already stolen the show, thanks to the radiant singing of Greek soprano Elena Kelessidi. Tu, che di gel and particularly Signore ascolta showed her voice in prime condition, with a secure top, and she performed with great pathos.

Having tenor Ben Heppner in the role of Calaf is somewhat of a treat, considering that he has only sung it once before (ten years ago in Chicago). He attacked the notes with power and force, taking a while to warm up in Act 1 but doing a good job of conveying the mental strain of the Riddle Scene. Let's face it: the tenor's success in this opera depends on how well he sings Nessun dorma, and Heppner rose to the challenge with panache. I also thought that there was an absence of the strain and cracked notes that had bothered some people (though not me) in last year's Otello.

The title role is more problematic. Georgina Lukács is an impressive figure on stage, and some of her top notes are remarkably powerful. She's also better looking than many sopranos in the part. However, when something more melodic is called for – In questa reggia or the closing duet, for instance – she wobbles about the tone without a clear sense of phrasing. It's nevertheless a good stab at an impossible character, who to me is psychologically inconsistent over the course of the opera.

Senior Artist Robert Lloyd returned to the role of Timur, Calaf's father, for the seventh time since the production's 1984 premiere, and was as vivid an actor as ever. A special mention is deserved by Francis Egerton, whose portrayal of the Emperor Altoum marks his last appearance with the company, after over 35 consecutive seasons and 750 performances in a range of roles. His characterful contributions will be sorely missed by ROH regulars.

It was also good to see Robbin Leggate back as Pang, with Ping played by Jorge Lagunes and Alasdair Elliott singing Pong. Vocally strong though they were, however, they could not overcome the excessive length and dramatic stasis of the opening of Act 2, which is the opera's weak spot.

It was a strong night for both chorus and orchestra, who provided the dramatic canvas for the work under the expert direction of Hungarian conductor Stefan Soltesz.

In all, despite some rough edges and occasional longueurs, this is an efficient revival of a Royal Opera classic.

- Dominic McHugh

Les Indes Galantes - Rameau - regia Andrei Serban - DVD movie

Director : Andrei Serban

Actors : Danielle De Niese - Anna Maria Panzarella - Patricia Petibon - William Christie - Nicolas Rivenq

Release date : August 2005

Actors : Danielle De Niese - Anna Maria Panzarella - Patricia Petibon - William Christie - Nicolas Rivenq

Release date : August 2005

Etichete:

1999,

LES INDES GALANTES,

Rameau Opera de Paris Garnier

luni, 1 septembrie 2008

Werther - Massenet on DVD (2005), regia Andrei Serban

Starring:

Vienna State Opera Orchestra Marcelo Alvarez Elina Garanca Philippe Jordan

Director:

Andrei Serban

A 2005 production of Massenet's opera which tells the tragic story of Werther's intense passion for Charlotte, who has married his best friend, Albert, fulfilling a pledge to her now deceased mother. But Werther's letters of love bring Charlotte to his side when he promises to take his own life. Philippe Jordan conducts the Vienna State Opera Orchestra

Etichete:

2005,

Massenet,

Werther,

Wiener Staatsoper

Rossini - L'Italiana In Algeri on DVD (1998), regia Andrei Serban

Starring:

Günter von Kannen Enric Serra Susan Maclean Rudolf Hartmann Anna-Maria Morgeli

Director:

Andrei Serban

Rossini's classic opera comic opera is one of the shining stars of the genre. Written when he was only twenty-one years old, L'ITALIANA IN ALGERI is a triumph of music and wit. This production was filmed at the Opera National De Paris in April 1998.

Etichete:

1998,

L'ITALIANA IN ALGERI,

Opera de Paris Garnier,

Rossini

King Stag, regia Andrei Serban

THEATER: 'KING STAG'

By MEL GUSSOW

Published: December 19, 1984

BOSTON ANDREI SERBAN has opened the season at the American Repertory Theater with a vivid production of Carlo Gozzi's Orientalized fairy tale, ''The King Stag.'' Filled with the marvelous costumes, masks and puppetry of Julie Taymor, this 18th-century charade should appeal to the fanciful at heart as well as the young in age.

At first glance, Gozzi would seem to be an anomaly, a traditionalist who was wedded to commedia del'arte at a time when his archrival, Carlo Goldoni, was advocating a more realistic, psychological approach to theater. Gozzi is best known today as the author of the original plays that inspired the Puccini and Prokofiev operas ''Turandot'' and ''The Love of Three Oranges,'' both of which Mr. Serban has directed in recent productions. This is Mr. Serban's season of Gozzi.

As the director demonstrates in ''The King Stag,'' Gozzi was an early Italian precursor of our contemporary fabulist theater, which takes ancient myths and turns them into relevant morality tales. It is a kind of pageantry that has been practiced by the Bread and Puppet Theater, the Talking Band and Miss Taymor herself.

Though one feels Mr. Serban's directorial imprint throughout the show, there are equal contributions from Miss Taymor and the set designer, Michael H. Yeargan. All three, collectively, have realized Gozzi's fantastical world.

''The King Stag'' transports us to the Kingdom of Serendippo, a court that is densely populated with plots and counterplots. The King is searching for a Queen, auditioning candidates rather than simply choosing Angela, who, alone among the applicants, loves the King rather than his kind. Soon we are on a royal hunt in the Forest of Miracoli where kingly souls mysteriously pass from human to animal form.

Each of the characters is emblematically masked and clothed; there is no confusing the heroes and the villains. The masks themselves are works of theatrical art, exceeded only by the puppets, which are as lifelike as Bunraku. From a talking parrot to a flying bear of huge proportions, they become an animated animal kingdom. Miss Taymor is able to project a considerable range of expression in her creatures, especially the figure of a feeble old man, who temporarily becomes the bony receptacle for the migratory soul of the handsome young king.

Behind the masks, one can spot the mimetic skills of Thomas Derrah as the King, Diane D'Aquila as his Queen to be, Dennis Bacigalupi, Lynn Chausow and Priscilla Smith. Miss Smith is cast as the comic villainess, a garish apparition who prides herself on her taste for ''hoot cootoor.''

Each is tutored in Mr. Serban's brand of commedia - bright and broad enough to be understood by the most youthful members of the audience. If ''The King Stag'' is, ultimately, not as much fun for adults as Mr. Serban's Moli ere melange, ''Sganarelle,'' it is because the text (adapted by Albert Bermel) is not on as frolicsome a level as the conceptualization.

For some odd reason, the director has decided to precede the 90-minute ''King Stag'' with an appetizer, a ''Gozzi Surprise.'' This 25-minute lampoon of the opera ''The Love of Three Oranges,'' is, in a word, a lemon. Fortunately, the main course is a festive holiday concoction.

Once Upon a Time THE KING STAG, by Carlo Gozzi; English version by Albert Bermel; directed by Andrei Serban; sets by Michael H. Yeargan; costumes, masks and puppetry by Julie Taymor; lighting by Jennifer Tipton; original music by Elliot Goldenthal. Presented by the American Repertory Theater, 64 Brattle Street, Cambridge, Mass. CigolottiJohn Bottoms DurandarteRodney Hudson BrighellaHarry S. Murphy SmeraldinaPriscilla Smith TruffaldinoDennis Bacigalupi TartagliaRichard Grusin ClariceLynn Chausow PantaloneJeremy Geidt AngelaDiane D'Aquila LeandroChristopher Moore DeramoThomas Derrah

By MEL GUSSOW

Published: December 19, 1984

BOSTON ANDREI SERBAN has opened the season at the American Repertory Theater with a vivid production of Carlo Gozzi's Orientalized fairy tale, ''The King Stag.'' Filled with the marvelous costumes, masks and puppetry of Julie Taymor, this 18th-century charade should appeal to the fanciful at heart as well as the young in age.

At first glance, Gozzi would seem to be an anomaly, a traditionalist who was wedded to commedia del'arte at a time when his archrival, Carlo Goldoni, was advocating a more realistic, psychological approach to theater. Gozzi is best known today as the author of the original plays that inspired the Puccini and Prokofiev operas ''Turandot'' and ''The Love of Three Oranges,'' both of which Mr. Serban has directed in recent productions. This is Mr. Serban's season of Gozzi.

As the director demonstrates in ''The King Stag,'' Gozzi was an early Italian precursor of our contemporary fabulist theater, which takes ancient myths and turns them into relevant morality tales. It is a kind of pageantry that has been practiced by the Bread and Puppet Theater, the Talking Band and Miss Taymor herself.

Though one feels Mr. Serban's directorial imprint throughout the show, there are equal contributions from Miss Taymor and the set designer, Michael H. Yeargan. All three, collectively, have realized Gozzi's fantastical world.

''The King Stag'' transports us to the Kingdom of Serendippo, a court that is densely populated with plots and counterplots. The King is searching for a Queen, auditioning candidates rather than simply choosing Angela, who, alone among the applicants, loves the King rather than his kind. Soon we are on a royal hunt in the Forest of Miracoli where kingly souls mysteriously pass from human to animal form.

Each of the characters is emblematically masked and clothed; there is no confusing the heroes and the villains. The masks themselves are works of theatrical art, exceeded only by the puppets, which are as lifelike as Bunraku. From a talking parrot to a flying bear of huge proportions, they become an animated animal kingdom. Miss Taymor is able to project a considerable range of expression in her creatures, especially the figure of a feeble old man, who temporarily becomes the bony receptacle for the migratory soul of the handsome young king.

Behind the masks, one can spot the mimetic skills of Thomas Derrah as the King, Diane D'Aquila as his Queen to be, Dennis Bacigalupi, Lynn Chausow and Priscilla Smith. Miss Smith is cast as the comic villainess, a garish apparition who prides herself on her taste for ''hoot cootoor.''

Each is tutored in Mr. Serban's brand of commedia - bright and broad enough to be understood by the most youthful members of the audience. If ''The King Stag'' is, ultimately, not as much fun for adults as Mr. Serban's Moli ere melange, ''Sganarelle,'' it is because the text (adapted by Albert Bermel) is not on as frolicsome a level as the conceptualization.

For some odd reason, the director has decided to precede the 90-minute ''King Stag'' with an appetizer, a ''Gozzi Surprise.'' This 25-minute lampoon of the opera ''The Love of Three Oranges,'' is, in a word, a lemon. Fortunately, the main course is a festive holiday concoction.

Once Upon a Time THE KING STAG, by Carlo Gozzi; English version by Albert Bermel; directed by Andrei Serban; sets by Michael H. Yeargan; costumes, masks and puppetry by Julie Taymor; lighting by Jennifer Tipton; original music by Elliot Goldenthal. Presented by the American Repertory Theater, 64 Brattle Street, Cambridge, Mass. CigolottiJohn Bottoms DurandarteRodney Hudson BrighellaHarry S. Murphy SmeraldinaPriscilla Smith TruffaldinoDennis Bacigalupi TartagliaRichard Grusin ClariceLynn Chausow PantaloneJeremy Geidt AngelaDiane D'Aquila LeandroChristopher Moore DeramoThomas Derrah

Review: Andrei Serban directs Irene Worth in ‘Happy days’

John D. Shout

The news that Andrei Serban was to attempt Happy days at the Public Theater in New York was greeted with a fair degree of scepticism. Serban, known most recently for startling ‘concept’ productions of The Trojan women, Agamemnon and The cherry orchard which struck some as highly offensive to the playwrights, intentions however momentarily engrossing they might be, is not a self-effacing director. Happy days, replete as it is with the most detailed directions (to say nothing of Beckett’s documentation of his own 1971 production), seems to defy directorial ingenuity. Beckett has tended to mistrust directors and Serban is not a man to leave a text alone. Happily—and surprisingly—the director has followed the playwright to the letter; shortly before the opening, he was quoted in The New York Times: ‘it would be idiotic to change Beckett around. He’s so precise every movement of the eyes, of the head.’ At least in conception and text he is completely faithful.

Beckett somewhat apologetically called Happy days ‘another misery,’ but it stands out in the canon, not only as his foremost vehicle for an actress but, arguably, as the most difficult to perform of any of the plays. With no one to interact with most of the time, the actress attempting Winnie must project everything subtextually, and should she fail the audience will be left with a muddled impression. In addition, she must avoid throughout the temptation to play for pathetic, half-witted comedy, lest she make Winnie merely a sand-covered version of Meg in The birthday party.

Despite her formidable predecessors—Ruth White, Madeleine Renaud and Dame Peggy Ashcroft among them—Irene Worth triumphs in the role. Some months before, she had had her first stab at Beckett in Narratives (at Harvard), an ill-conceived attempt to join Beckett texts to atonal chamber music. Only when she offered a wistful, brooding reading of the story of Mildred and her doll from the end of Happy days—to piano accompaniment—was the evening anything but calculated novelty. Now she is free to take the role in its own terms. Worth is an American actress whom American audiences regularly assume to be British, perhaps because of her many years with the Old Vic and the Royal Shakespeare Company. For whatever reason, her performance is nicely de-nationalized: her Winnie has British mannerisms (Winnie has been called Beckett’s most English character) without anything that seems unnaturally tacked on. Her accent is unidentifiable. Physically, she is the picture of Beckett’s own description.

Worth is most captivating in her moments of pure mime; one can clearly see why she finds Winnie ‘the closest to Charlie’s tramp that you can get.’ But her Winnie is so realistically composed that her thoughts and words seem perfectly natural for a middle-aged woman with a cluttered mind. She is amusing throughout and unlike other Winnies she appears fully conscious of the irony of her situation. The quotations in the ‘sweet old style’ are delivered with a touch of asperity and with little genuine conviction. She regards her encounters with Mr. Johnson-Johnston and Mr. and Mrs. Shower-Cooker with a sort of sarcasm that rules out self-pity. Only on rare occasion does she weaken and then it’s only for the briefest moment. For some tastes, she—or Serban—may carry this strength too far. This is a cold conception of Happy days (recalling Serban’s broad and unfeeling The cherry orchard), one denying Winnie her occasional moments of dithering pathos.

The only warmth in the character is evoked by her Willie (competently played by George Voskovec) about whom she is never ironic. The ending of Happy days is its major ambiguity: is Willie trying to reach Winnie or the gun, and if the gun, to use it on her or on himself? Serban is not definite, but clearly Willie will succeed in reaching nothing; he ludicrously attempts several climbs up the mound but always slides back making no progress. At last he gives up the struggle and Winnie watches him with an expression of concern and devotion. Here too Serban seems determined to alienate us.

Michael Yeargan and Lawrence King have created a lunar landscape that suggests that there are other offstage mounds, and their sky (with Jennifer Tipton’s lighting) is a heavenly and artificial blue, in sharp contrast to the orange sky—dating from the Paris production—that some have preferred. In short, this Happy days is not at all dispiriting but not deeply moving either. Irene Worth’s Winnie is neither deluded nor conventional, and she is sentimental only with Willie who is the real buffoon here. One cannot always accept a performer’s description of what he finds in his role, but in this case Irene Worth has very accurately realized her own description: ‘She represents mankind, the stamina of man and the triumph of the spirit. She rejoices in the life force. Things get her down, but she never feels sorry for herself. She springs back in a symbolic way.’ Whether this is the Winnie one usually imagines is another question.

The news that Andrei Serban was to attempt Happy days at the Public Theater in New York was greeted with a fair degree of scepticism. Serban, known most recently for startling ‘concept’ productions of The Trojan women, Agamemnon and The cherry orchard which struck some as highly offensive to the playwrights, intentions however momentarily engrossing they might be, is not a self-effacing director. Happy days, replete as it is with the most detailed directions (to say nothing of Beckett’s documentation of his own 1971 production), seems to defy directorial ingenuity. Beckett has tended to mistrust directors and Serban is not a man to leave a text alone. Happily—and surprisingly—the director has followed the playwright to the letter; shortly before the opening, he was quoted in The New York Times: ‘it would be idiotic to change Beckett around. He’s so precise every movement of the eyes, of the head.’ At least in conception and text he is completely faithful.

Beckett somewhat apologetically called Happy days ‘another misery,’ but it stands out in the canon, not only as his foremost vehicle for an actress but, arguably, as the most difficult to perform of any of the plays. With no one to interact with most of the time, the actress attempting Winnie must project everything subtextually, and should she fail the audience will be left with a muddled impression. In addition, she must avoid throughout the temptation to play for pathetic, half-witted comedy, lest she make Winnie merely a sand-covered version of Meg in The birthday party.

Despite her formidable predecessors—Ruth White, Madeleine Renaud and Dame Peggy Ashcroft among them—Irene Worth triumphs in the role. Some months before, she had had her first stab at Beckett in Narratives (at Harvard), an ill-conceived attempt to join Beckett texts to atonal chamber music. Only when she offered a wistful, brooding reading of the story of Mildred and her doll from the end of Happy days—to piano accompaniment—was the evening anything but calculated novelty. Now she is free to take the role in its own terms. Worth is an American actress whom American audiences regularly assume to be British, perhaps because of her many years with the Old Vic and the Royal Shakespeare Company. For whatever reason, her performance is nicely de-nationalized: her Winnie has British mannerisms (Winnie has been called Beckett’s most English character) without anything that seems unnaturally tacked on. Her accent is unidentifiable. Physically, she is the picture of Beckett’s own description.

Worth is most captivating in her moments of pure mime; one can clearly see why she finds Winnie ‘the closest to Charlie’s tramp that you can get.’ But her Winnie is so realistically composed that her thoughts and words seem perfectly natural for a middle-aged woman with a cluttered mind. She is amusing throughout and unlike other Winnies she appears fully conscious of the irony of her situation. The quotations in the ‘sweet old style’ are delivered with a touch of asperity and with little genuine conviction. She regards her encounters with Mr. Johnson-Johnston and Mr. and Mrs. Shower-Cooker with a sort of sarcasm that rules out self-pity. Only on rare occasion does she weaken and then it’s only for the briefest moment. For some tastes, she—or Serban—may carry this strength too far. This is a cold conception of Happy days (recalling Serban’s broad and unfeeling The cherry orchard), one denying Winnie her occasional moments of dithering pathos.

The only warmth in the character is evoked by her Willie (competently played by George Voskovec) about whom she is never ironic. The ending of Happy days is its major ambiguity: is Willie trying to reach Winnie or the gun, and if the gun, to use it on her or on himself? Serban is not definite, but clearly Willie will succeed in reaching nothing; he ludicrously attempts several climbs up the mound but always slides back making no progress. At last he gives up the struggle and Winnie watches him with an expression of concern and devotion. Here too Serban seems determined to alienate us.

Michael Yeargan and Lawrence King have created a lunar landscape that suggests that there are other offstage mounds, and their sky (with Jennifer Tipton’s lighting) is a heavenly and artificial blue, in sharp contrast to the orange sky—dating from the Paris production—that some have preferred. In short, this Happy days is not at all dispiriting but not deeply moving either. Irene Worth’s Winnie is neither deluded nor conventional, and she is sentimental only with Willie who is the real buffoon here. One cannot always accept a performer’s description of what he finds in his role, but in this case Irene Worth has very accurately realized her own description: ‘She represents mankind, the stamina of man and the triumph of the spirit. She rejoices in the life force. Things get her down, but she never feels sorry for herself. She springs back in a symbolic way.’ Whether this is the Winnie one usually imagines is another question.

Spovedanie la Tanacu, regia Andrei Serban

Jurnalistul Mirel Bran relateaza pentru Cotidianul care a fost impactul premierei de la New York a piesei "Spovedania", pusa in scena de Andrei Serban dupa romanul scris de Tatiana Niculescu Bran.

Andrei Serban (foto, in dreapta) crede ca aceasta piesa povesteste Romania intr-un mod fara precedent

(FOTO: Daniela Dima)

In momentul in care aplauzele si ovatiile au izbucnit in sala teatrului La MaMa, de la New York, am inteles cu totii ca tot ce ni se intimpla era adevarat. Piesa de teatru "Spovedania", tradusa, pentru publicul american, prin "Deadly Confession", pe care sotia mea, Tatiana Niculescu Bran, o scrisese pentru regizorul Andrei Serban, si o mina de tineri actori din Romania au ridicat in picioare publicul unei sali mitice din vecinatatea Broadway-ului.

La inceputul acestei aventuri s-a aflat cartea "Spovedanie la Tanacu", un roman jurnalistic publicat la Editura Humanitas, in toamna anului 2006. Scrisa in urma unei anchete amanuntite a cazului Tanacu, aceasta carte avea sa devina materia prima a piesei de teatru care ne-a adus pe toti la premiera programata pe 1 octombrie si organizata de Institutul Cultural Roman din New York.

Initiata de Corina Suteu, presedinta Asociatiei ECUMEST si directoarea ICRNY de la New York, "Academia itineranta Andrei Serban" a debutat cu dramatizarea si punerea in scena a acestei carti. "Este prima piesa de teatru care povesteste Romania de astazi intr-un mod cu totul nou, ne-a marturisit Andrei Serban. Teatrul romanesc are nevoie de un suflu proaspat, precum cel din cinematografie, adus de noua generatie de regizori. Aceasta piesa poate marca un inceput". Atelierul cu actorii si primele improvizatii pe marginea textului cartii s-au facut in iulie, la Plopi, un sat izolat din Muntii Apuseni, unde regizorul s-a retras impreuna cu actorii si cu autoarea cartii pentru a dramatiza "Spovedanie la Tanacu".

Nu cunosteam bine mediul actoricesc din Romania si am fost cu atit mai surprins de profesionalismul acestor tineri actori proveniti din diverse teatre din provincie. Urma sa fiu martorul unui experiment teatral care mi-a desfiintat toate cliseele pe care le aveam despre creatia teatrala. Ca prim exercitiu, la Plopi, Andrei Serban i-a invitat pe actori sa dramatizeze ei insisi scene din carte si sa le joace. Pe masura ce ei improvizau scenele, autoarea "Spovedaniei la Tanacu" scria textul piesei de teatru inspirindu-se din jocul lor. "Deadly Confession" nu a fost scrisa inainte de a fi jucata, ci in timp ce se juca. Probabil ca tocmai acest efort colectiv a condus la un text cu o incarcatura care depaseste cu mult cadrul unui fapt divers local.

Lucrul a continuat in sala teatrului La MaMa din Manhattan, care a gazduit, in cei 46 de ani de existenta, unele dintre cele mai interesante experimente teatrale americane si internationale. Pe 1 octombrie a fost rindul Romaniei sa prezinte o creatie teatrala originala. Cu o seara inainte, prudent, Andrei Serban i-a prevenit pe actori ca publicul american, in general, e zgircit cu laudele si nu e obisnuit sa aplaude indelung la finalul unei reprezentatii. In seara urmatoare, la finalul piesei jucate cu maiestrie si cu mare finete actoriceasca, publicul newyorkez s-a ridicat in picioare electrizat si a aplaudat minute in sir, strigind "Bravo!". Povestea unei tentative de alungare a duhurilor rele despre care s-a scris enorm si nu s-a inteles aproape nimic a convins exigentul public american de calitatea creatiei teatrale din Romania.

La Bucuresti se vor ridica probabil voci care ii vor infiera pe protagonistii acestei creatii, acuzindu-i ca strica imaginea Romaniei. Cred insa ca tinerii actori romani care au exaltat publicul american au invatat un lucru mai pretios decit discursurile propagandistice, si anume ca talentul lor incepe sa fie apreciat pe marile scene ale lumii.

Dupa premiera de la New York, piesa de teatru "Spovedania" asteapta sa fie preluata de un teatru din Romania. Am filmat aventura facerii ei in amanunt cu gindul unui film documentar pe care il voi propune spre difuzare canalului de televiziune TVR 1 la inceputul anului viitor."

· Academia Itineranta

Andrei Serban Travelling Academy (Academia Itineranta) este un proiect initiat si finantat de Asociatia ECUMEST si de Institutul Cultural Roman din New York. Miza acestuia este sa aduca laolalta scriitori, actori si regizori, in cadrul unui laborator de creatie. Andrei Serban, una dintre cele mai importante figuri ale teatrului din secolul XX, este cel care coordoneaza acest workshop. Actori: Csilla Albert, Richard Balint, Ionut Caras, Ramona Dumitrean, Cristian Grosu, Catalin Herlo, Cristina Holtzli, Silvius Iorga, Mara Opris, Florentina Tilea, Andrea Tokai.

Andrei Serban (foto, in dreapta) crede ca aceasta piesa povesteste Romania intr-un mod fara precedent

(FOTO: Daniela Dima)

In momentul in care aplauzele si ovatiile au izbucnit in sala teatrului La MaMa, de la New York, am inteles cu totii ca tot ce ni se intimpla era adevarat. Piesa de teatru "Spovedania", tradusa, pentru publicul american, prin "Deadly Confession", pe care sotia mea, Tatiana Niculescu Bran, o scrisese pentru regizorul Andrei Serban, si o mina de tineri actori din Romania au ridicat in picioare publicul unei sali mitice din vecinatatea Broadway-ului.

La inceputul acestei aventuri s-a aflat cartea "Spovedanie la Tanacu", un roman jurnalistic publicat la Editura Humanitas, in toamna anului 2006. Scrisa in urma unei anchete amanuntite a cazului Tanacu, aceasta carte avea sa devina materia prima a piesei de teatru care ne-a adus pe toti la premiera programata pe 1 octombrie si organizata de Institutul Cultural Roman din New York.

Initiata de Corina Suteu, presedinta Asociatiei ECUMEST si directoarea ICRNY de la New York, "Academia itineranta Andrei Serban" a debutat cu dramatizarea si punerea in scena a acestei carti. "Este prima piesa de teatru care povesteste Romania de astazi intr-un mod cu totul nou, ne-a marturisit Andrei Serban. Teatrul romanesc are nevoie de un suflu proaspat, precum cel din cinematografie, adus de noua generatie de regizori. Aceasta piesa poate marca un inceput". Atelierul cu actorii si primele improvizatii pe marginea textului cartii s-au facut in iulie, la Plopi, un sat izolat din Muntii Apuseni, unde regizorul s-a retras impreuna cu actorii si cu autoarea cartii pentru a dramatiza "Spovedanie la Tanacu".

Nu cunosteam bine mediul actoricesc din Romania si am fost cu atit mai surprins de profesionalismul acestor tineri actori proveniti din diverse teatre din provincie. Urma sa fiu martorul unui experiment teatral care mi-a desfiintat toate cliseele pe care le aveam despre creatia teatrala. Ca prim exercitiu, la Plopi, Andrei Serban i-a invitat pe actori sa dramatizeze ei insisi scene din carte si sa le joace. Pe masura ce ei improvizau scenele, autoarea "Spovedaniei la Tanacu" scria textul piesei de teatru inspirindu-se din jocul lor. "Deadly Confession" nu a fost scrisa inainte de a fi jucata, ci in timp ce se juca. Probabil ca tocmai acest efort colectiv a condus la un text cu o incarcatura care depaseste cu mult cadrul unui fapt divers local.

Lucrul a continuat in sala teatrului La MaMa din Manhattan, care a gazduit, in cei 46 de ani de existenta, unele dintre cele mai interesante experimente teatrale americane si internationale. Pe 1 octombrie a fost rindul Romaniei sa prezinte o creatie teatrala originala. Cu o seara inainte, prudent, Andrei Serban i-a prevenit pe actori ca publicul american, in general, e zgircit cu laudele si nu e obisnuit sa aplaude indelung la finalul unei reprezentatii. In seara urmatoare, la finalul piesei jucate cu maiestrie si cu mare finete actoriceasca, publicul newyorkez s-a ridicat in picioare electrizat si a aplaudat minute in sir, strigind "Bravo!". Povestea unei tentative de alungare a duhurilor rele despre care s-a scris enorm si nu s-a inteles aproape nimic a convins exigentul public american de calitatea creatiei teatrale din Romania.

La Bucuresti se vor ridica probabil voci care ii vor infiera pe protagonistii acestei creatii, acuzindu-i ca strica imaginea Romaniei. Cred insa ca tinerii actori romani care au exaltat publicul american au invatat un lucru mai pretios decit discursurile propagandistice, si anume ca talentul lor incepe sa fie apreciat pe marile scene ale lumii.

Dupa premiera de la New York, piesa de teatru "Spovedania" asteapta sa fie preluata de un teatru din Romania. Am filmat aventura facerii ei in amanunt cu gindul unui film documentar pe care il voi propune spre difuzare canalului de televiziune TVR 1 la inceputul anului viitor."

· Academia Itineranta

Andrei Serban Travelling Academy (Academia Itineranta) este un proiect initiat si finantat de Asociatia ECUMEST si de Institutul Cultural Roman din New York. Miza acestuia este sa aduca laolalta scriitori, actori si regizori, in cadrul unui laborator de creatie. Andrei Serban, una dintre cele mai importante figuri ale teatrului din secolul XX, este cel care coordoneaza acest workshop. Actori: Csilla Albert, Richard Balint, Ionut Caras, Ramona Dumitrean, Cristian Grosu, Catalin Herlo, Cristina Holtzli, Silvius Iorga, Mara Opris, Florentina Tilea, Andrea Tokai.

duminică, 31 august 2008

Ana Maria Narti - "Medeea lui Andrei Serban"

Teatrul să ia foc!

Doresc să fac două comentarii: unul despre subiect, altul despre autoarea acestui studiu.Medeea - acest proiect îşi are originea în lucrul pe care l-am făcut cu Brook şi Centrul său de Cercetare Teatrală de la Paris. Aceasta a fost inspiraţia directă. Dar, în spirit, proiectul a început dinainte, încă din Institut, pe vremea când eram student la clasa lui Penciulescu. Am citit recent în revista Teatrul azi o declaraţie a lui Radu Penciulescu în care afirmă că, de fapt, clasa noastră de regizori studenţi de pe vremea aceea a constituit începutul noului val al teatrului românesc. Dacă e aşa, de ce teatrul cu adevărat nou a început tocmai cu noi?! Eu cred că din cauza lui Rică Manea şi a lui Ivan Helmer şi a celorlalţi, care s-au pus pe carte serios, drept care cu toţii am citit, cot la cot, cu profesorul nostru tot ce era disponibil din dramaturgia şi teoria radicală a anilor '60.Şi, pentru că am pus multă poftă şi pasiune în a ne crea o viziune, am devorat cărţile, iar ele au devenit iute pretexte de spectacole-examen care mai de care mai deşuchiate, mai libere şi lipsite de logica convenţiei realismului atât de mult promovat. Manea a făcut Lecţia, un spectacol dement, tulburător, eu Ubu (în care Manea juca), unde nu exista nici o limită a ceea e posibil, nici o relaţie cu realul, totul era violent exploziv, comic, dar pus în relaţie cu forţe cosmice iraţionale, nu la un comic de situaţii obişnuite, un teritoriu în care îţi pierdeai busola, nu mai ştiai unde te situezi, te simţeai invadat, şi totuşi erai acolo, credeai în ceea ce se întâmplă, intrai în joc şi te lăsai prins de acel iureş de energii irezistibile. Medeea s-a născut, fără să ştiu în acel moment, pe băncile şcolii de regie, sub impresia lecturilor din Artaud, a ritmurilor şi sunetelor care să provoace subconştientul ca să devină vizibil, actorul să devină magician şi teatrul să ia foc.Brook a văzut probabil în mine resurse pe care eu nu ştiam că le posed.Am fost norocos. Dacă eu nu regizam la New York Arden din Faversham, şi Brook nu venea, din întâmplare, la Teatrul "La Mama" în seara premierei să dea ca exemplu, apoi, că a văzut în Arden cea mai clară montare după ideile expuse în Le théâtre et son double, dacă el vedea, în loc de Arden, Lecţia lui Manea - destinul fiecăruia poate ar fi fost altul... Oricum, Medeea a fost regizoral "clocită" chiar pe meleagurile unde odată se spune că ar fi călătorit chiar ea...Ana Maria Narti a fost de la începutul carierei mele, încă din studenţie, întâi o cronicară ce evalua extrem de just spectacolele, atât pe ale mele, cât şi pe ale altora, apoi o prietenă şi o colaboratoare cu care (împreună cu alţii) am format iute o comunitate teatrală restrânsă. Eram cu toţii tineri pe atunci şi puteam simţi ce avem în comun. Astăzi, aici, în climatul românesc de acum ceva lipseşte; poate că dispariţia acelui spirit "de gaşcă artistică" ar trebui să fie recunoscută mai profund. Dar atunci, împreună cu Ana Maria şi cu câţiva actori şi scenografi, ne dădeam seama că lucrul trebuie făcut în comun. Apelul era comun. Drumul era comun. Aşa e firesc şi sănătos să fie în teatru în orice situaţie: poate expresia individuală a fiecăruia e specială, dar e mai puternică dacă este împărtăşită în comun. După atâţia ani de experienţă, pot afirma cu siguranţă că relaţia se produce dacă devenim conştienţi că singuri nu suntem capabili de nimic şi că e o necesitate extremă de a ne întâlni (scriitori, actori, critici, dramaturgi, toţi care vor să găsească "altceva"), pentru a stabili împreună o relaţie cu noul sau necunoscutul. Acest exemplu al unei comunităţi create spontan pe baze de simpatie nu l-am mai regăsit uşor după aceea, din clipa când am început să lucrez în marile teatre ale lumii sau în instituţiile de operă. Dar nici o personalitate critică de calibrul Anei Maria Narti nu se afla pe toate drumurile. Cine în deşertul criticii româneşti din acest moment (minus câteva excepţii) se poate compara cu Narti? Într-o atmosferă plină de fasoane şi capricii, de mofturi pseudointelectuale şi luări de poziţie sub efectul subiectivismului de moment şi al lipsei de observaţie riguroasă, exemplul unui critic care să aducă ceva nou, care să inspire o viziune şi să definească o cale nu prea există. Şi întâlnirea cu Narti a fost un noroc, căci, pe lângă faptul că lucram la texte împreună, iar ea ilumina multe aspecte proaspete de care mă foloseam în repetiţii, era şi un cronicar extrem de bine pregătit, profund şi clar, dar scria cronici din iubire faţă de profesiune şi scria cu inteligenţă combinată cu o caldă afecţiune. Lucrul la Medeea nu ar fi fost acelaşi fără prezenţa ei activă şi spiritul ei rece de observaţie.Medeea a avut o viaţă lungă. Dar la început, nu credeam că se va juca mai mult de două săptămâni. Cine va veni, ne întrebam, să vadă un grup de şapte actori incantând la lumina lumânărilor cuvinte de neînţeles, în greaca veche a lui Euripide şi în latina lui Seneca? De aceea, am conceput spectacolul pentru treizeci şi cinci de spectatori în subsolul de la "La Mama", crezând că nici măcar beciul acela strâmt nu îl vom putea umple. După câteva luni, jucam în ruinele de la Baalbek, în Liban, pentru o mie de spectatori, iar mai târziu ne-am trezit pe vârful muntelui Lycabetos, la Atena, jucând - pe stânca albă, luminaţi de luna plină - pentru două mii de greci avizi de sunete pe care nici ei nu le înţelegeau, ca să trecem mai târziu prin diverse văi şi pe munţi chiar mai înalţi, ca la Verbier, un loc celebru de schi în Alpii elveţieni, unde am jucat în condiţii extrem de speciale. Acolo a fost poate versiunea cea mai misterioasă dintre toate..., căci, în timpul celor 55 de minute cât durează Medeea, s-a coborât un nor dens şi toţi, actori şi public, am fost prinşi în ceaţă în aşa fel, că nu ne mai vedeam deloc unii pe alţii. Nu doar spectatorii pe actori, ci nimeni nu-l mai vedea nici chiar pe cel care îi era alături... Medeea şi Iason se auzeau doar..., copiii erau omorâţi în cer... şi asta nu era o metaforă sau un simbol... cum e încă la modă, din păcate, în teatrul de avangardă din România... Am jucat în grote în Bretania, în ruinele de la Persepolis, în muzee de artă modernă, într-un fost abator la Viena, într-un bar de noapte la Copenhaga, într-un grajd lângă Amsterdam, la Bouffes şi la Chaillot la Paris, într-o mânăstire din Lisabona, pe malul Atlanticului, ori într-o piaţă acoperită din Sao Paolo. Peste tot, spiritul aventurii şi dorinţa de a descoperi prin teatru un limbaj universal, dincolo de cultură, dincolo de prejudecăţi naţionale, ne-a întărit şi ne-a format pe noi, ca artişti şi, în primul rând, ca oameni. Prin sunetul tragediei greceşti, ceva în noi s-a deschis. Teatrul devenea un ajutor, un exemplu pentru o evoluţie posibilă.Privesc în urmă. Au trecut de la repetiţiile cu Medeea la New York aproape treizeci şi cinci de ani. Am revenit să lucrez în România acum şaptesprezece ani, iar Trilogia a contribuit ca teatrul românesc să facă un pas major spre viitor.Şi totuşi, controversa în ce mă priveşte continuă. Deşi sunt la o vârstă când ar trebui să mi se recunoască un anumit statut, continuu să fiu privit drept un provocator care supără şi deranjează.Mă întreb ce ar fi fost dacă aş fi conceput Medeea iniţial la Bucureşti, fără să fi ajuns vreodată la New York şi la "La Mama". Fără ştampila şi binecuvântarea lui Brook, cum ar fi fost primită? Faptul că sunt considerat şi azi un subversiv incomod mă face să zâmbesc. Deşi aş prefera să am linişte şi să fiu aplaudat de toţi, controversa care continuă mă face să mă simt încă în acea gaşcă cu care eram împreună cu Ana Maria acum o jumătate de secol. Poate că astfel bătrâneţea întârzie să vină.(Cluj, iunie 2007) - Andrei Serban, in prefata cartii

Doresc să fac două comentarii: unul despre subiect, altul despre autoarea acestui studiu.Medeea - acest proiect îşi are originea în lucrul pe care l-am făcut cu Brook şi Centrul său de Cercetare Teatrală de la Paris. Aceasta a fost inspiraţia directă. Dar, în spirit, proiectul a început dinainte, încă din Institut, pe vremea când eram student la clasa lui Penciulescu. Am citit recent în revista Teatrul azi o declaraţie a lui Radu Penciulescu în care afirmă că, de fapt, clasa noastră de regizori studenţi de pe vremea aceea a constituit începutul noului val al teatrului românesc. Dacă e aşa, de ce teatrul cu adevărat nou a început tocmai cu noi?! Eu cred că din cauza lui Rică Manea şi a lui Ivan Helmer şi a celorlalţi, care s-au pus pe carte serios, drept care cu toţii am citit, cot la cot, cu profesorul nostru tot ce era disponibil din dramaturgia şi teoria radicală a anilor '60.Şi, pentru că am pus multă poftă şi pasiune în a ne crea o viziune, am devorat cărţile, iar ele au devenit iute pretexte de spectacole-examen care mai de care mai deşuchiate, mai libere şi lipsite de logica convenţiei realismului atât de mult promovat. Manea a făcut Lecţia, un spectacol dement, tulburător, eu Ubu (în care Manea juca), unde nu exista nici o limită a ceea e posibil, nici o relaţie cu realul, totul era violent exploziv, comic, dar pus în relaţie cu forţe cosmice iraţionale, nu la un comic de situaţii obişnuite, un teritoriu în care îţi pierdeai busola, nu mai ştiai unde te situezi, te simţeai invadat, şi totuşi erai acolo, credeai în ceea ce se întâmplă, intrai în joc şi te lăsai prins de acel iureş de energii irezistibile. Medeea s-a născut, fără să ştiu în acel moment, pe băncile şcolii de regie, sub impresia lecturilor din Artaud, a ritmurilor şi sunetelor care să provoace subconştientul ca să devină vizibil, actorul să devină magician şi teatrul să ia foc.Brook a văzut probabil în mine resurse pe care eu nu ştiam că le posed.Am fost norocos. Dacă eu nu regizam la New York Arden din Faversham, şi Brook nu venea, din întâmplare, la Teatrul "La Mama" în seara premierei să dea ca exemplu, apoi, că a văzut în Arden cea mai clară montare după ideile expuse în Le théâtre et son double, dacă el vedea, în loc de Arden, Lecţia lui Manea - destinul fiecăruia poate ar fi fost altul... Oricum, Medeea a fost regizoral "clocită" chiar pe meleagurile unde odată se spune că ar fi călătorit chiar ea...Ana Maria Narti a fost de la începutul carierei mele, încă din studenţie, întâi o cronicară ce evalua extrem de just spectacolele, atât pe ale mele, cât şi pe ale altora, apoi o prietenă şi o colaboratoare cu care (împreună cu alţii) am format iute o comunitate teatrală restrânsă. Eram cu toţii tineri pe atunci şi puteam simţi ce avem în comun. Astăzi, aici, în climatul românesc de acum ceva lipseşte; poate că dispariţia acelui spirit "de gaşcă artistică" ar trebui să fie recunoscută mai profund. Dar atunci, împreună cu Ana Maria şi cu câţiva actori şi scenografi, ne dădeam seama că lucrul trebuie făcut în comun. Apelul era comun. Drumul era comun. Aşa e firesc şi sănătos să fie în teatru în orice situaţie: poate expresia individuală a fiecăruia e specială, dar e mai puternică dacă este împărtăşită în comun. După atâţia ani de experienţă, pot afirma cu siguranţă că relaţia se produce dacă devenim conştienţi că singuri nu suntem capabili de nimic şi că e o necesitate extremă de a ne întâlni (scriitori, actori, critici, dramaturgi, toţi care vor să găsească "altceva"), pentru a stabili împreună o relaţie cu noul sau necunoscutul. Acest exemplu al unei comunităţi create spontan pe baze de simpatie nu l-am mai regăsit uşor după aceea, din clipa când am început să lucrez în marile teatre ale lumii sau în instituţiile de operă. Dar nici o personalitate critică de calibrul Anei Maria Narti nu se afla pe toate drumurile. Cine în deşertul criticii româneşti din acest moment (minus câteva excepţii) se poate compara cu Narti? Într-o atmosferă plină de fasoane şi capricii, de mofturi pseudointelectuale şi luări de poziţie sub efectul subiectivismului de moment şi al lipsei de observaţie riguroasă, exemplul unui critic care să aducă ceva nou, care să inspire o viziune şi să definească o cale nu prea există. Şi întâlnirea cu Narti a fost un noroc, căci, pe lângă faptul că lucram la texte împreună, iar ea ilumina multe aspecte proaspete de care mă foloseam în repetiţii, era şi un cronicar extrem de bine pregătit, profund şi clar, dar scria cronici din iubire faţă de profesiune şi scria cu inteligenţă combinată cu o caldă afecţiune. Lucrul la Medeea nu ar fi fost acelaşi fără prezenţa ei activă şi spiritul ei rece de observaţie.Medeea a avut o viaţă lungă. Dar la început, nu credeam că se va juca mai mult de două săptămâni. Cine va veni, ne întrebam, să vadă un grup de şapte actori incantând la lumina lumânărilor cuvinte de neînţeles, în greaca veche a lui Euripide şi în latina lui Seneca? De aceea, am conceput spectacolul pentru treizeci şi cinci de spectatori în subsolul de la "La Mama", crezând că nici măcar beciul acela strâmt nu îl vom putea umple. După câteva luni, jucam în ruinele de la Baalbek, în Liban, pentru o mie de spectatori, iar mai târziu ne-am trezit pe vârful muntelui Lycabetos, la Atena, jucând - pe stânca albă, luminaţi de luna plină - pentru două mii de greci avizi de sunete pe care nici ei nu le înţelegeau, ca să trecem mai târziu prin diverse văi şi pe munţi chiar mai înalţi, ca la Verbier, un loc celebru de schi în Alpii elveţieni, unde am jucat în condiţii extrem de speciale. Acolo a fost poate versiunea cea mai misterioasă dintre toate..., căci, în timpul celor 55 de minute cât durează Medeea, s-a coborât un nor dens şi toţi, actori şi public, am fost prinşi în ceaţă în aşa fel, că nu ne mai vedeam deloc unii pe alţii. Nu doar spectatorii pe actori, ci nimeni nu-l mai vedea nici chiar pe cel care îi era alături... Medeea şi Iason se auzeau doar..., copiii erau omorâţi în cer... şi asta nu era o metaforă sau un simbol... cum e încă la modă, din păcate, în teatrul de avangardă din România... Am jucat în grote în Bretania, în ruinele de la Persepolis, în muzee de artă modernă, într-un fost abator la Viena, într-un bar de noapte la Copenhaga, într-un grajd lângă Amsterdam, la Bouffes şi la Chaillot la Paris, într-o mânăstire din Lisabona, pe malul Atlanticului, ori într-o piaţă acoperită din Sao Paolo. Peste tot, spiritul aventurii şi dorinţa de a descoperi prin teatru un limbaj universal, dincolo de cultură, dincolo de prejudecăţi naţionale, ne-a întărit şi ne-a format pe noi, ca artişti şi, în primul rând, ca oameni. Prin sunetul tragediei greceşti, ceva în noi s-a deschis. Teatrul devenea un ajutor, un exemplu pentru o evoluţie posibilă.Privesc în urmă. Au trecut de la repetiţiile cu Medeea la New York aproape treizeci şi cinci de ani. Am revenit să lucrez în România acum şaptesprezece ani, iar Trilogia a contribuit ca teatrul românesc să facă un pas major spre viitor.Şi totuşi, controversa în ce mă priveşte continuă. Deşi sunt la o vârstă când ar trebui să mi se recunoască un anumit statut, continuu să fiu privit drept un provocator care supără şi deranjează.Mă întreb ce ar fi fost dacă aş fi conceput Medeea iniţial la Bucureşti, fără să fi ajuns vreodată la New York şi la "La Mama". Fără ştampila şi binecuvântarea lui Brook, cum ar fi fost primită? Faptul că sunt considerat şi azi un subversiv incomod mă face să zâmbesc. Deşi aş prefera să am linişte şi să fiu aplaudat de toţi, controversa care continuă mă face să mă simt încă în acea gaşcă cu care eram împreună cu Ana Maria acum o jumătate de secol. Poate că astfel bătrâneţea întârzie să vină.(Cluj, iunie 2007) - Andrei Serban, in prefata cartii

The New York Times, cronica la The Merchant of Venice, ianuarie 1999

THEATER REVIEW; From Serban, The Shylock Of Yesteryear, A Go-To Guy

Let Shylock be Shylock! is the unspoken motto of Andrei Serban's daringly unapologetic production of ''The Merchant of Venice.''

Shed no tears for the Jewish moneylender of Mr. Serban's design. Shylock may be cruelly maligned by the Christian hypocrites in Shakespeare's difficult play, with its anti-Semitic overtones, but in this version he has hardly been conceived as a figure to touch the heart. Though it has become customary to render Shylock with compassion, as in Peter Hall's 1989 Broadway production, in which Dustin Hoffman's dignified pillar of a Shylock endured the taunts and a shower of spittle from his enemies, Mr. Serban breaks with modern practice and gives us something more like the sinister Shylock of yore.

Thanks to the capable conjuring of the actor Will LeBow, Shylock is imagined in this visually striking modern-dress staging at the American Repertory Theater as a Venetian go-to guy who holds the beautiful people of the canals in as much contempt as they hold him. (The performance might appeal to the literary critic Harold Bloom, who in his new book on Shakespeare argues for just such a ''comic villain'' of a Shylock).

Just how spiteful a piece of work is this villain is revealed in Mr. LeBow's rendition of the famous ''Hath not a Jew eyes?'' speech. Routinely treated as a plea for understanding, it is instead delivered here as a caustic act of self-mockery, intended to patronize his bigoted audience, the Venetian dilettantes Solanio (Stephen Rowe) and Salerio (Jeremy Geidt).

Only when the embittered loan shark has them laughing along with him does his voice rise in sudden anguish and fury: ''And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge?'' That this is a man who savors his singleminded pursuit of his pound of flesh is never in doubt; in the climactic courtroom scene, where he is called upon to claim the flesh owed him by the merchant Antonio (a shrewdly lugubrious Jonathan Epstein), he even draws a circle in red on the torso of his victim and theatrically traces it with a knife.

The sleek affability of Mr. LeBow's seductive portrayal imbues this Shylock with a visceral authority, a power to make things happen, which also makes him the most compelling feature of Mr. Serban's often absorbing production. But ''The Merchant of Venice'' is much more than the tale of a moneylender's humiliation; its more central concern is the romantic comedy of the wooing of Portia (Kristin Flanders) by Bassanio (Andrew Garman) and other sillier suitors. It's these lighter moments that trip up Mr. Serban, who seems much more in his element elucidating the cosmic complexities of ''Merchant'' than in realizing the gently comic ironies in the love story.

It may be that the hideous resolution of the Shylock subplot -- can an enlightened audience identify with a heroine who utters lines like ''Tarry, Jew'' or feel anything but squeamishness at Shylock's forced conversion? -- insinuates itself like an odor that can't be washed out. Still, Mr. Serban, who did such a fine job in Central Park last summer framing the humane qualities in Shakespeare's troublesome ''Cymbeline,'' has his actors take wide swings at the comic interludes, like overeager croquet players. The result is a tactlessness that undoes some of the production's finer points.

''Merchant'' is in part about the unraveling of riddles in language and law and the unmasking of people who are not what they seem. In this vein, the scenes encompassing the elaborate riddle that Portia poses for her suitors are bizarrely broad and consequently sophomoric; the young actors portraying princes from Morocco and Spain, for instance, are encouraged to play cartoon characters who throw off the play's rhythms, and Ms. Flanders and Portia's lady-in-waiting Nerissa (Nurit Monicelli), engage in an affected style of banter at an unnecessary remove from sincerity. While the play has Portia outwitting Shylock in court, Ms. Flanders never manages to challenge Mr. LeBow for primacy onstage.

Mr. Serban is a restless experimenter, so his Shakespearean ventures tend to be jampacked with ideas good and less good. One of his best notions here is the decadent and sexually ambiguous world of Antonio, the merchant of the title, who takes the disastrous loan from Shylock, with its peculiar terms, to finance the effort of his friend Bassanio to romance Portia.

The beauty of Venice and Belmont, as suggested by the Adriatic pastels in the lovely folding screens by Marielle Bancou and William Bonnell and lighting by Michael Chybowski, turns out to be a mirage. The scenic charm is as superficial as the slick, two-faced Venetian businessmen themselves, who make deals with the Jewish moneylender, only to revile him behind his back. (At a costume ball, they even resort to garish masks with exaggerated Semitic noses.) Dressing them all in natty European suits, it seems, is a reminder by Mr. Serban and his inventive costume designer, Catherine Zuber, that empty-headed bigotry has many contemporary disguises.

In this false paradise, Mr. Serban finds little to romanticize. Portia sermonizes grandly to Shylock about the quality of mercy, but she and the rest of Venice are complicit in a merciless dismemberment of Shylock's fortune, his faith, his very identity. It is the director's eloquent thesis, in fact, that Shylock and his Venetian tormentors are more alike than different; the vengeance envisioned by Shylock is symbolically carried out by his Christian adversaries. To drive home the point, perhaps unnecessarily, Mr. Serban creates a final dumb show in which Antonio -- who by Portia's verdict appropriates Shylock's wealth -- is locked in a dance with the masked Shylock. The borrower and the lender are now as one. Mr. Serban's uneven cast is an impediment. Several of the younger actors simply do not add their own pound of flesh to these mysterious characters, which gives the play an only partly lived-in quality. As he did with Liev Schreiber's vital Iachimo in ''Cymbeline,'' though, the director finds in Mr. LeBow a lead actor who helps us greatly in our navigation of the dark side. THE MERCHANT OF VENICE By William Shakespeare; directed by Andrei Serban; music composed by Elizabeth Swados; sets by Christine Jones; screen designs by Marielle Bancou and William Bonnell; costumes by Catherine Zuber; lighting by Michael Chybowski; sound by Christopher Walker; musical direction by Michael Friedman. Presented by the American Repertory Theater, Cambridge, Mass.

Let Shylock be Shylock! is the unspoken motto of Andrei Serban's daringly unapologetic production of ''The Merchant of Venice.''

Shed no tears for the Jewish moneylender of Mr. Serban's design. Shylock may be cruelly maligned by the Christian hypocrites in Shakespeare's difficult play, with its anti-Semitic overtones, but in this version he has hardly been conceived as a figure to touch the heart. Though it has become customary to render Shylock with compassion, as in Peter Hall's 1989 Broadway production, in which Dustin Hoffman's dignified pillar of a Shylock endured the taunts and a shower of spittle from his enemies, Mr. Serban breaks with modern practice and gives us something more like the sinister Shylock of yore.

Thanks to the capable conjuring of the actor Will LeBow, Shylock is imagined in this visually striking modern-dress staging at the American Repertory Theater as a Venetian go-to guy who holds the beautiful people of the canals in as much contempt as they hold him. (The performance might appeal to the literary critic Harold Bloom, who in his new book on Shakespeare argues for just such a ''comic villain'' of a Shylock).

Just how spiteful a piece of work is this villain is revealed in Mr. LeBow's rendition of the famous ''Hath not a Jew eyes?'' speech. Routinely treated as a plea for understanding, it is instead delivered here as a caustic act of self-mockery, intended to patronize his bigoted audience, the Venetian dilettantes Solanio (Stephen Rowe) and Salerio (Jeremy Geidt).

Only when the embittered loan shark has them laughing along with him does his voice rise in sudden anguish and fury: ''And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge?'' That this is a man who savors his singleminded pursuit of his pound of flesh is never in doubt; in the climactic courtroom scene, where he is called upon to claim the flesh owed him by the merchant Antonio (a shrewdly lugubrious Jonathan Epstein), he even draws a circle in red on the torso of his victim and theatrically traces it with a knife.

The sleek affability of Mr. LeBow's seductive portrayal imbues this Shylock with a visceral authority, a power to make things happen, which also makes him the most compelling feature of Mr. Serban's often absorbing production. But ''The Merchant of Venice'' is much more than the tale of a moneylender's humiliation; its more central concern is the romantic comedy of the wooing of Portia (Kristin Flanders) by Bassanio (Andrew Garman) and other sillier suitors. It's these lighter moments that trip up Mr. Serban, who seems much more in his element elucidating the cosmic complexities of ''Merchant'' than in realizing the gently comic ironies in the love story.

It may be that the hideous resolution of the Shylock subplot -- can an enlightened audience identify with a heroine who utters lines like ''Tarry, Jew'' or feel anything but squeamishness at Shylock's forced conversion? -- insinuates itself like an odor that can't be washed out. Still, Mr. Serban, who did such a fine job in Central Park last summer framing the humane qualities in Shakespeare's troublesome ''Cymbeline,'' has his actors take wide swings at the comic interludes, like overeager croquet players. The result is a tactlessness that undoes some of the production's finer points.

''Merchant'' is in part about the unraveling of riddles in language and law and the unmasking of people who are not what they seem. In this vein, the scenes encompassing the elaborate riddle that Portia poses for her suitors are bizarrely broad and consequently sophomoric; the young actors portraying princes from Morocco and Spain, for instance, are encouraged to play cartoon characters who throw off the play's rhythms, and Ms. Flanders and Portia's lady-in-waiting Nerissa (Nurit Monicelli), engage in an affected style of banter at an unnecessary remove from sincerity. While the play has Portia outwitting Shylock in court, Ms. Flanders never manages to challenge Mr. LeBow for primacy onstage.

Mr. Serban is a restless experimenter, so his Shakespearean ventures tend to be jampacked with ideas good and less good. One of his best notions here is the decadent and sexually ambiguous world of Antonio, the merchant of the title, who takes the disastrous loan from Shylock, with its peculiar terms, to finance the effort of his friend Bassanio to romance Portia.

The beauty of Venice and Belmont, as suggested by the Adriatic pastels in the lovely folding screens by Marielle Bancou and William Bonnell and lighting by Michael Chybowski, turns out to be a mirage. The scenic charm is as superficial as the slick, two-faced Venetian businessmen themselves, who make deals with the Jewish moneylender, only to revile him behind his back. (At a costume ball, they even resort to garish masks with exaggerated Semitic noses.) Dressing them all in natty European suits, it seems, is a reminder by Mr. Serban and his inventive costume designer, Catherine Zuber, that empty-headed bigotry has many contemporary disguises.

In this false paradise, Mr. Serban finds little to romanticize. Portia sermonizes grandly to Shylock about the quality of mercy, but she and the rest of Venice are complicit in a merciless dismemberment of Shylock's fortune, his faith, his very identity. It is the director's eloquent thesis, in fact, that Shylock and his Venetian tormentors are more alike than different; the vengeance envisioned by Shylock is symbolically carried out by his Christian adversaries. To drive home the point, perhaps unnecessarily, Mr. Serban creates a final dumb show in which Antonio -- who by Portia's verdict appropriates Shylock's wealth -- is locked in a dance with the masked Shylock. The borrower and the lender are now as one. Mr. Serban's uneven cast is an impediment. Several of the younger actors simply do not add their own pound of flesh to these mysterious characters, which gives the play an only partly lived-in quality. As he did with Liev Schreiber's vital Iachimo in ''Cymbeline,'' though, the director finds in Mr. LeBow a lead actor who helps us greatly in our navigation of the dark side. THE MERCHANT OF VENICE By William Shakespeare; directed by Andrei Serban; music composed by Elizabeth Swados; sets by Christine Jones; screen designs by Marielle Bancou and William Bonnell; costumes by Catherine Zuber; lighting by Michael Chybowski; sound by Christopher Walker; musical direction by Michael Friedman. Presented by the American Repertory Theater, Cambridge, Mass.

Benvenuto Cellini, Berlioz regia Andrei Serban, cronica din The New York Times

Since its troubled premiere at the Paris Opera in 1838, Berlioz's ''Benvenuto Cellini'' has intrigued and befuddled opera companies, stage directors and audiences. It's a curious work -- call it an epic historical comedy -- that exists in several conflicting versions. And it either boldly or confusingly (depending upon your perspective) juxtaposes diverse operatic styles in trying to tell the story of Cellini, the 16th-century Italian sculptor, goldsmith, miscreant and self-aggrandizing memoirist.

Many conductors enormously respect the score, which abounds with inventive and engaging music. But over the years not many companies have stepped up to produce it. I've encountered the work only twice: the 1975 American premiere by the Opera Company of Boston under Sarah Caldwell with Jon Vickers in the title role, and on Thursday night at the Metropolitan Opera.

It was the opening of the company's first production ever, by the director Andrei Serban in his Met debut, with James Levine conducting and the tenor Marcello Giordani in the title role. This is the second installment of the Met's celebration of the 200th anniversary of Berlioz's birth, the first being ''Les Troyens'' last spring.

Mr. Serban's production crowds the stage with dancers, extras, surreal props and more commedia dell'arte antics than you would have thought possible to fit into a night at the opera. When he and the production team, including the set designer George Tsypin and the costume designer Georgi Alexi-Meskhishvili, took their joint curtain call, they were greeted by a mixed chorus of lusty boos and ardent bravos, which essentially encapsulated my own reactions.

The clumsy plot focuses on a breakthrough moment in Cellini's life, when he was about to cast the monumental statue of Perseus with the severed head of Medusa. In the opera, Pope Clement VII has commissioned the work over the opposition of his scheming Vatican treasurer, Balducci, who favors a mediocrity, the sculptor Fieramosca, whom he plans to marry to his lovely young daughter, Teresa. But Teresa is smitten with Cellini. The ensuing story tells of Cellini's attempt to hoodwink Balducci, win Teresa, secure a pardon for inadvertently stabbing a monk at a brawl -- and cast his statue, a feat he pulls off in the triumphant final scene.

Berlioz extracted his popular ''Roman Carnival Overture,'' from portions of ''Benvenuto Cellini,'' which takes place in Rome during revels for Shrove Monday, and Mr. Serban's production is like a three-ring circus.

The set is dominated by a huge, rotating, semicircular house of translucent marble with twin twisting staircases. Scaffolding and ladders lean against the inside walls, bringing to mind those Renaissance paintings in which ladders symbolize the arduous route to heaven.

A constant swarm of commedia dell'arte characters flit across the stage and poke out of windows. In a heavy-handed touch, Berlioz, in the person of a red-haired, lanky man in a 19th-century waistcoat, wanders about the stage observing the action and jotting down notes.

In his Met debut, the choreographer Nikolaus Wolcz has devised some stylized, jerky movements for a roster of brawny men who portray Cellini's fellow metalworkers. At one point two Adonislike youths appear wielding swords and wearing nothing but fig leaves: idealized apparitions of Perseus and Medusa? It may not have made sense, but you can bet that for about 10 minutes most people in the house were not paying much attention to their Met Titles.

Still, however fanciful or alluring the antics and images, there is just too much going on. Apparently the staging was even more cluttered before Mr. Serban was prevailed upon by the Met to thin things out a bit.

His work stood in contrast to Mr. Levine's, who captured the score's high spirits but also its subtlety, tenderness and grandeur. The music constantly surprises you with its shifting meters, elusive rhythms and roving harmonies.

Even the comedic bits are often delicate and graceful, for example, the gossamer trio in the first scene, sung by Cellini, Teresa and the hidden Fieramosca. Would that more of those qualities had been reflected in the staging.

Many conductors enormously respect the score, which abounds with inventive and engaging music. But over the years not many companies have stepped up to produce it. I've encountered the work only twice: the 1975 American premiere by the Opera Company of Boston under Sarah Caldwell with Jon Vickers in the title role, and on Thursday night at the Metropolitan Opera.

It was the opening of the company's first production ever, by the director Andrei Serban in his Met debut, with James Levine conducting and the tenor Marcello Giordani in the title role. This is the second installment of the Met's celebration of the 200th anniversary of Berlioz's birth, the first being ''Les Troyens'' last spring.

Mr. Serban's production crowds the stage with dancers, extras, surreal props and more commedia dell'arte antics than you would have thought possible to fit into a night at the opera. When he and the production team, including the set designer George Tsypin and the costume designer Georgi Alexi-Meskhishvili, took their joint curtain call, they were greeted by a mixed chorus of lusty boos and ardent bravos, which essentially encapsulated my own reactions.

The clumsy plot focuses on a breakthrough moment in Cellini's life, when he was about to cast the monumental statue of Perseus with the severed head of Medusa. In the opera, Pope Clement VII has commissioned the work over the opposition of his scheming Vatican treasurer, Balducci, who favors a mediocrity, the sculptor Fieramosca, whom he plans to marry to his lovely young daughter, Teresa. But Teresa is smitten with Cellini. The ensuing story tells of Cellini's attempt to hoodwink Balducci, win Teresa, secure a pardon for inadvertently stabbing a monk at a brawl -- and cast his statue, a feat he pulls off in the triumphant final scene.

Berlioz extracted his popular ''Roman Carnival Overture,'' from portions of ''Benvenuto Cellini,'' which takes place in Rome during revels for Shrove Monday, and Mr. Serban's production is like a three-ring circus.

The set is dominated by a huge, rotating, semicircular house of translucent marble with twin twisting staircases. Scaffolding and ladders lean against the inside walls, bringing to mind those Renaissance paintings in which ladders symbolize the arduous route to heaven.

A constant swarm of commedia dell'arte characters flit across the stage and poke out of windows. In a heavy-handed touch, Berlioz, in the person of a red-haired, lanky man in a 19th-century waistcoat, wanders about the stage observing the action and jotting down notes.

In his Met debut, the choreographer Nikolaus Wolcz has devised some stylized, jerky movements for a roster of brawny men who portray Cellini's fellow metalworkers. At one point two Adonislike youths appear wielding swords and wearing nothing but fig leaves: idealized apparitions of Perseus and Medusa? It may not have made sense, but you can bet that for about 10 minutes most people in the house were not paying much attention to their Met Titles.

Still, however fanciful or alluring the antics and images, there is just too much going on. Apparently the staging was even more cluttered before Mr. Serban was prevailed upon by the Met to thin things out a bit.

His work stood in contrast to Mr. Levine's, who captured the score's high spirits but also its subtlety, tenderness and grandeur. The music constantly surprises you with its shifting meters, elusive rhythms and roving harmonies.

Even the comedic bits are often delicate and graceful, for example, the gossamer trio in the first scene, sung by Cellini, Teresa and the hidden Fieramosca. Would that more of those qualities had been reflected in the staging.

Etichete:

2003,

Opera Review December 6,

The New York Times

Articol despre Andrei Serban in presa americana

Not for All Time

As the A.R.T. begins rehearsal for Pericles, Arthur Holmberg setsAndrei Serban's Shakespeare productions in historical context.

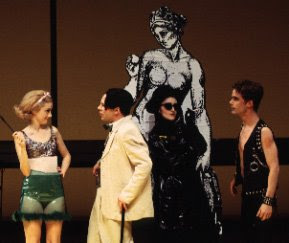

Above:The Merchant of Venice (1998)

Above & below: The Taming of the Shrew (1998)

The past hundred years will go down in theatre history as the age of the director. Although the twentieth century also produced great playwrights, the emergence of the auteur director sets modern drama apart from all previous ages of theatre. In many respects, the evolution of twentieth-century theatre has been driven by auteur directors, directors who have contributed much to what is distinctive about modern theatre. The term "auteur director" was borrowed from French film criticism and means that the director is the author of the theatrical event.

During the past century, directors as much as playwrights have created the new forms that characterize the restlessness of modern drama: Realism, Symbolism, Futurism, Surrealism, Expressionism, and the Theatre of Images. Stanislavsky and Meyerhold, Artaud and Brecht (as director), Peter Brook and Robert Wilson - these artists gave as much to the rich variety of our theatrical traditions as did playwrights. Some scholars, in fact, consider Brecht as director more influential than Brecht as playwright. One cannot write the history of our theatre without acknowledging that the modern director is an artist in his or her own right.

Whereas students of film accept as dogma the auteur director, in theatre his emergence has sparked squabbles and lawsuits. Whose play is it anyway? Much ink has been spilled in classrooms and courtrooms over this issue. In one of the notorious controversies of contemporary theatre, Samuel Beckett tried to shut down the A.R.T.'s production of Endgame. The playwright damned the direction of JoAnne Akalaitis as heresy. Beckett objected to a racially mixed cast and to the set design, both of which he felt distracted the audience from his text.Beckett's dismay raises serious questions about interpretation, artistic collaboration, and the complex relationship between text and performance. Behind all these concerns, and often unacknowledged, lies the great conflict: which is more important, word or image, ear or eye? A play does not exist in a book one reads in a library. As the British director Jonathan Miller notes, performance is a constitutive part of the identity of a play. A play exists only in performance, and performances that rethink a text with strong visual images provoke debate.

Nowhere does this controversy come into sharper focus than in the plays of Shakespeare, the most canonical playwright of the canon and Armageddon of the word-image war. Shakespeare, in fact, has attracted auteur directors like moths to a flame. To be writ large in the history of theatre, one must climb Mt. Everest, and many of the landmark productions that prompted shifts in performance styles have originated with Shakespeare.

These productions have also altered how we understand Shakespeare's plays. In Changing Styles in Shakespeare Ralph Berry asserts that in the last generation, "The most interesting and influential reappraisals of certain plays have been launched by performances." Peter Brook's King Lear, for example, brought that play into the absurd universe of Beckett. The stage has assumed a higher intellectual profile with the rise to power of the director who reinterprets classics from a forceful stance. "Wrestling physically with a great dramatic text - working out the problems of how to do it - is a form of sustained, detailed literary critcism," declares Jonathan Miller, who produced two years of the Shakespeare plays on PBS and directed Sheridan's The School for Scandal at the A.R.T.

Not everyone, however, approves of this need to reinterpret the past. "Young man, how dare you meddle with Our Shakespeare?" snarled a distraught dowager at Nigel Playfair's 1920 futurist As You Like It. The indignation continues, and so does the "meddling," undaunted. Even if we had enough information (we do not) to reconstruct a performance of Shakespeare exactly as done in his day, it would not work.

When applied to theatre, Roman Jakobson's model of verbal communication helps explain how theatre functions. In "Linguistics and Poetics," Jakobson lists six factors in any speech event: addresser, addressee, message, shared code, context and contact ("a physical channel and psychological connection between addresser and addressee, enabling both of them to enter and stay in communication.")

In terms of Shakespeare and a contemporary audience, all six factors present problems that militate against communication. Code, context, and contact have obviously suffered a sea change. But the question of addresser, message, and addressee is not as simple as first appears. We are not the addressees of Shakespeare's message.

Twelfth Night (1989)Cherry Jones and Diane Lane

In The Role of the Reader, Umberto Eco notes that each text postulates a Model Reader. The Model Spectator postulated by Shakespeare's plays does not correspond to anyone alive, well, and living in Cambridge. But the patrons of the Globe were not the addressees either. The addressee of Shakespeare's texts was the company of actors he wrote for. Shakespeare conceived of his plays as a script to perform. His "foul papers" were a cluster of instructions for a specific group of actors to act. Thus, he showed no interest in having the plays published. Shakespeare did not write his texts for us. We have them by chance and happenstance, and we will never have them in a completely reliable state.

My purpose is to illustrate the difficulty of trying to think of Shakespeare as the addresser of the message and us as the addressee. We are eavesdropping on a message sent to someone else. Many problems fall into place if we conceive of the cycle of communication that Shakespeare initiated as having ended once the troupe of actors he wrote for got his manuscript. The message in the bottle is sent to actors, not audience. After the actors receive the playwright's message, they set in motion a new cycle of communication in which they, the actors, are the addressers and the audience the addressee.

These two cycles are closely related and one is dependent on the other, but they remain two distinct cycles of communication. Unlike readers of a novel, the theatre audience can never be the addressee of the playwright. The point of contact for communication in theatre is the theatre. Put differently, the playwright's message must be performed, and performance is interpretation, representation, mediation. For this reason, Shakespeare speaks not for an age, but for all time. Only through fresh interpretations can he remain alive for succeeding generations. His plays are not just a historical document. They are a challenge to every great director to breathe new theatrical life into them so that they can live in the minds and hearts of new audiences.